I wanted to put down a few thoughts about what I've seen from Japanese director Sono Shion. I thought of putting them up in my

Tetsuo thread in movies, but since I'm really more looking at them from a "culture notes" point of view, perhaps this is better.

I'm specifically looking at his films 「自殺サークル」(

Jisatsu Saakuru, variously translated as "Suicide Circle" and "Suicide Club") and 「紀子の食卓」(

Noriko no Shokutoku, "Noriko's Dinner Table"). They are the first parts of a planned trilogy and marketed as horror films. The first certainly is, indeed it's a "splatter" film, though I liked it despite not being a fan of that genre. In general, I'm finding Japanese horror movies far better than American, but it's quite possible this is mostly due to picking those singled out for recommendation in Swan's reviews. "Noriko," the pre/sequel is a tougher call. Someone expecting a gorefest might well be disappointed by it, but in many ways its themes are even more horrific.

I'll try to avoid major spoilers herein, but a few minor ones are unavoidable. Indeed, I think the "Noriko" trailer actually ruins a nice reveal, but it's not a show-stopper.

"Suicide Club" opens with a sequence of 54 high school girls joining hands and cheerfully jumping in front of a train at Shinjuku station. This is the first of a series of mass suicides marked by either cheerfulness or seeming disregard on the parts of the victims. The police are initially unsure whether to treat the incidents as suicides or murders, though there are indications of some organization behind them (notably the grisly contents of sports bags found at the scene and a website that keeps a running total, updating before the official announcements).

Average age 12.5 years.

Average age 12.5 years.It does seem a bit of a plot hole that the police don't investigate the website angle more thoroughly, but that line does lead to telephone contact with a seemingly knowledgeable but surprising party. There are also hints that a preteen girl group may somehow figure into it all (I was pleased to see that someone in Japan appreciates the essential creepiness of that phenomenon). The group's name, "Dessert," is spelled "Desaat" the first time we see it. That's the most likely way a Japanese would misspell it, but I was already impressed enough with Sono to wonder if he knew what he was doing. He did. The name is misspelled every time we see it, but never the same way twice.

Welcome to my pleasure room!

Welcome to my pleasure room!Note that there are one or two subtly confusing subtitles, but nothing that should really confuse you for long. By the way, there is one truly brutal scene midway through involving a rape/murder and cruelty to small animals. Make no mistake, this isn't a kids' film. I find the scene disturbing, though I believe it's justified.

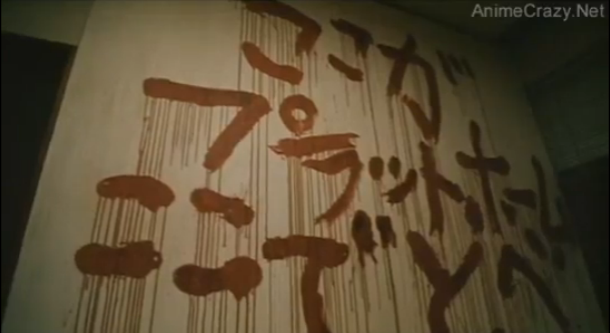

Here is the platform. Jump here.

Here is the platform. Jump here.That aside, this middle portion of the film is very satisfying if you like mystery; expect the unexpected. This is what I like about J-horror, also the fact that it doesn't seem to feel that the answer to every question must be spelled out. Indeed, the film's surreal climax involves a series of questions that seem to be central to what Sono is on about. The setting and questioner are key to the scene's effectiveness, but if I say more that

will be a spoiler:

何しに来たんですか?

Nani shi ni kita'n desu ka?What have you come here to do?

あなたはあなたとの関係を修復しに来たのですか?

Anata ha anata to no kankei wo shuufuku shi ni kita no desu ka?Are you one who came to mend the connection with yourself?

あなたはあなたとの関係を切りに来たのですか?

Anata ha anata to no kankei wo kiri ni kita no desu ka?Are you one who came to cut the connection with yourself?

あなたはあなたに関係のないあなたですか?

Anata ha anata ni kankei no nai anata desu ka?Are you someone who has no connection with yourself?

On first seeing this film, I was amazed to see something so subversive come out of Japan. As Americans, we revel in questioning our society. Indeed, I think we may sometimes go overboard on this, in that we become so used to the questions that we don't bother to ponder the answers, or become satisfied with pre-packaged mass-produced ones (like the ones from the entertainment industry about the evils of greed and overconsumption, leading to a warm sense of moral superiority and a tremendous urge to buy something over-priced yet "green"). Japanese society and culture most definitely don't encourage this kind of self-assessment, and I was interested in the way Sono presented them. You can take "Suicide Club" as nothing more than a riot of splashing fake blood if you wish, but there's something much more deeply unsettling if you're open to it.

And then came "Suicide Club 2: Noriko's Dinner Table," in which Sono sprang his trap.

The movie opens with 17-year-old Noriko Shimabara arriving in Tokyo, having run away from what she sees as a stifling home life with her parents and sister in the countryside. She had only ever felt truly connected to the girls she met on the haikyo.com message board (the meaning is "ruins" or "remains," and is shown to be connected to the website from the previous movie). Overwhelmed and alone, she goes to a net cafe to PM moderator "Ueno Station 54" to ask if she will meet her in person.

Noriko's virtual friends: Broken Dam, Cripple #5, Long Neck, Midnight & Ueno Station 54. Shadows more real than her family.

Noriko's virtual friends: Broken Dam, Cripple #5, Long Neck, Midnight & Ueno Station 54. Shadows more real than her family.Adopting her screen name of "Mitsuko," she now begins a new life with Ueno Station, who runs a "rental family" business in which actors go to people's homes and pretend to be their ideal family. I've never heard of this actually being done, but it seems a logical extension of

enjou kosai or "compensated dating." This phenomenon involved typically middle-aged men paying young girls to go out with them, sometimes as a cover for prostitution to be sure, but also with a sense of fighting a pathetic loneliness.

Stray cats form families immediately. No need to feel sorry for them. They're tough. They own this town.

Stray cats form families immediately. No need to feel sorry for them. They're tough. They own this town.In addition to Ueno Station's fascinating back-story, the movie also returns to Noriko's family back in Akita as it painfully and subliminally disintegrates. Tetsuzo, the father, finally quits his job at the local paper and sets out on a quest for those responsible. This leads to a stellar sequence in which he finds an answer that seems to further illuminate Sono's theme:

It's time for you to wake up to your role. Who are you? You said you were connected to yourself, but are you really? You're not believable as a reporter or a father. The world is full of lies, roles that people can't play convincingly. They fail as husbands, wives, fathers, mothers, etc. So, the only way to figure out what we can be is to lie openly and pursue emptiness. Feel the desert. Experience loneliness. Feel it. Survive the desert. That is your role. Once upon a time there was a baby who was born in a coin locker.

Once upon a time there was a baby who was born in a coin locker.All I'll say about the end is that it plays out "the circle of life."

Now it's true that Shakespeare wrote: "All the world's a stage, and all the men and women merely players . . . " but what is metaphorical in Western culture is much closer to literal in Japanese. "Suicide Club" could be viewed as a denunciation of the anomie and valuelessness of modern culture (a favorite idea of the Japanese Right, among many others), but "Noriko" turns the spotlight squarely on the Japanese family. I believe that most Americans see themselves as individuals who happen to belong to families, while for Japanese the family is far more central to their individual identity. And yet, the traditional values of propriety and hierarchy define it as thoroughly as they do Japan's corporate culture. Communication tends to be implicit rather than explicit. Japanese mothers don't offer their kids a choice of -- say -- ice cream flavors; the ideal is that they should know the child's favorite and give it to them without asking. But what about a parent like Tetsuzo, who "understands nothing about his family except that he understands nothing about them"? I'm convinced that Sono is not presenting the Shimabaras as dysfunctional through some peculiarity, but through their very typicality.

A lot of Japanese horror/sci fi revolves around characters bent on destroying the world (often portrayed surprisingly sympathetically), but the question that seems to run through these movies is whether there is truly any world worth destroying.

It's been some years now since "Noriko's" release in '05. I hope the third film gets made. I really want to see Sono's final word on this.

Edit:

On reflection, I should make clear that Sono is not a nihilist in the sense of "therefore there is no morality and cruelty is no less justified than anything else." Genesis (the "pleasure room" guy above) is a personification of this attitude, and if Sono sees him as anything other than a cruel egotist I'm mis-reading him.

Sono wonders if there's any "there" there, but the end of "Noriko" might even be read as happy from the characters' points of view. Most get what they want, while one realizes that not everyone wants the same thing.

But one reason I wish Sono would make the third is that "Suicide Club" reads very differently after one has seen "Noriko," and I suspect the third would shed new light on both.